Today, we’d like to introduce you to Dana VanderLugt.

Hi Dana, can you start by introducing yourself? We’d love to learn more about how you got to where you are today.

I am a writer and teacher who descends from a family of Michigan apple growers and storytellers.

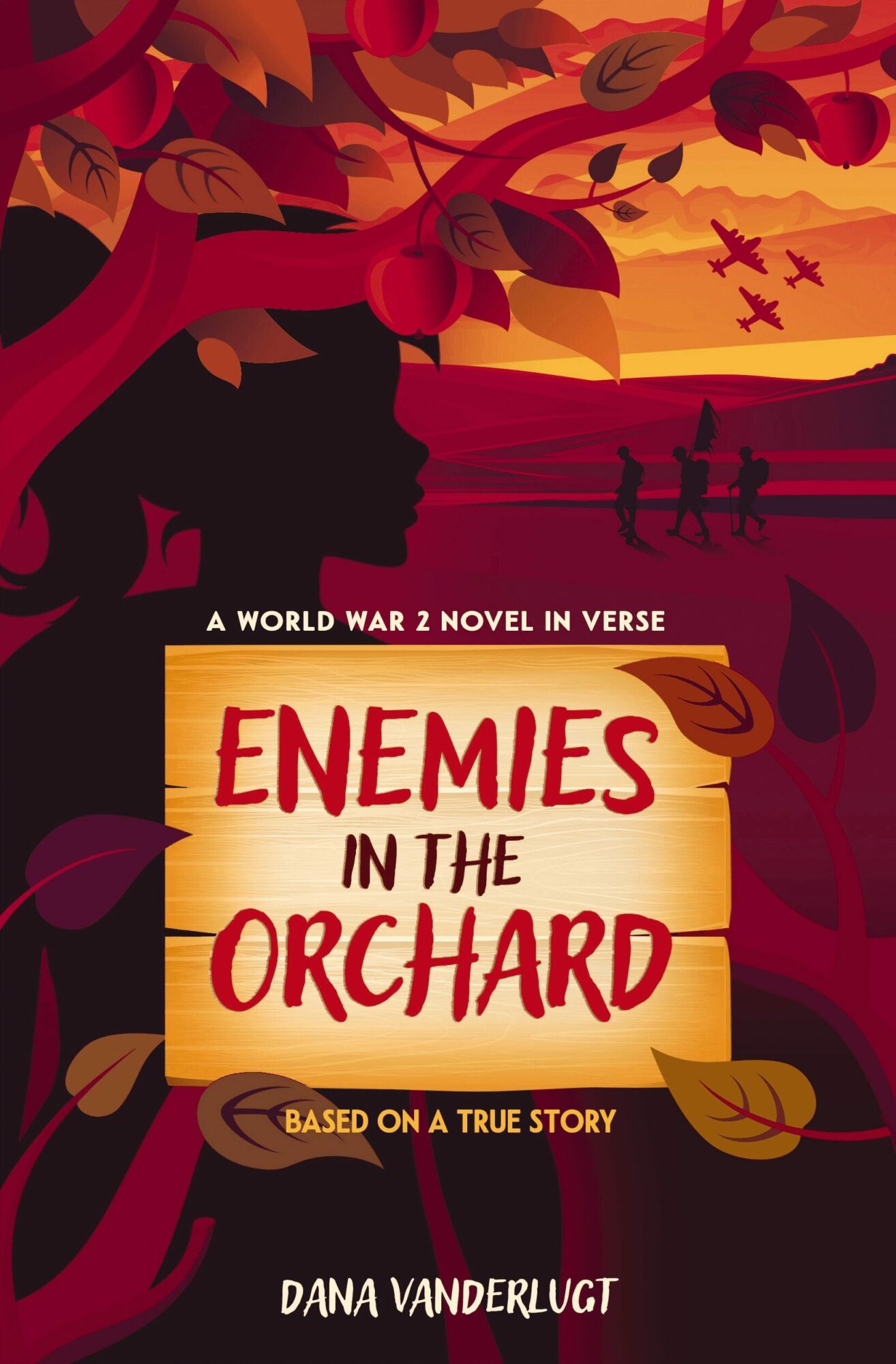

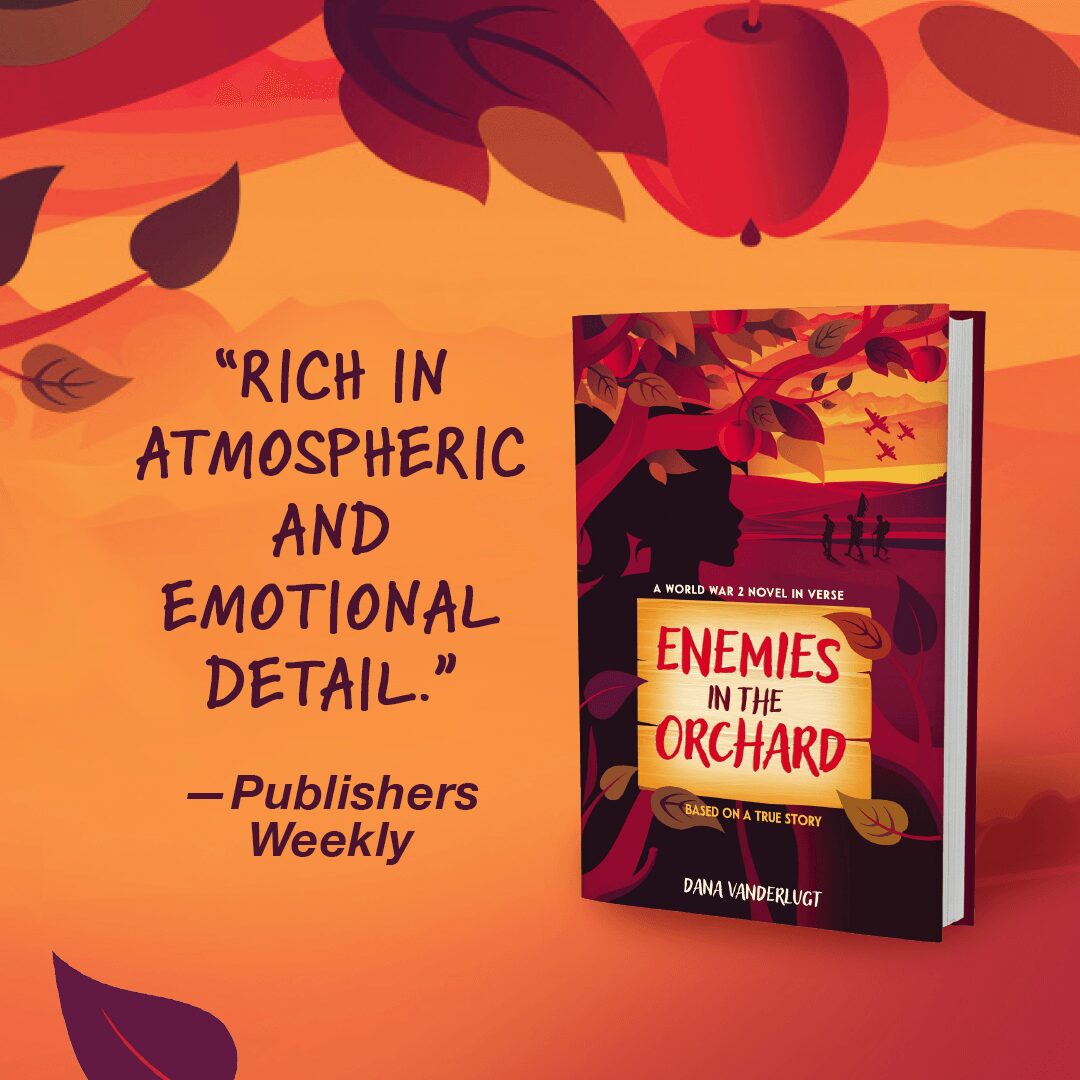

My book, Enemies in the Orchard: A World War 2 Novel in Verse, was released in the fall of 2023 and delves into the little-known history of German Prisoners of War who were brought to the United States in the 1940s as an answer to our country’s wartime labor shortage.

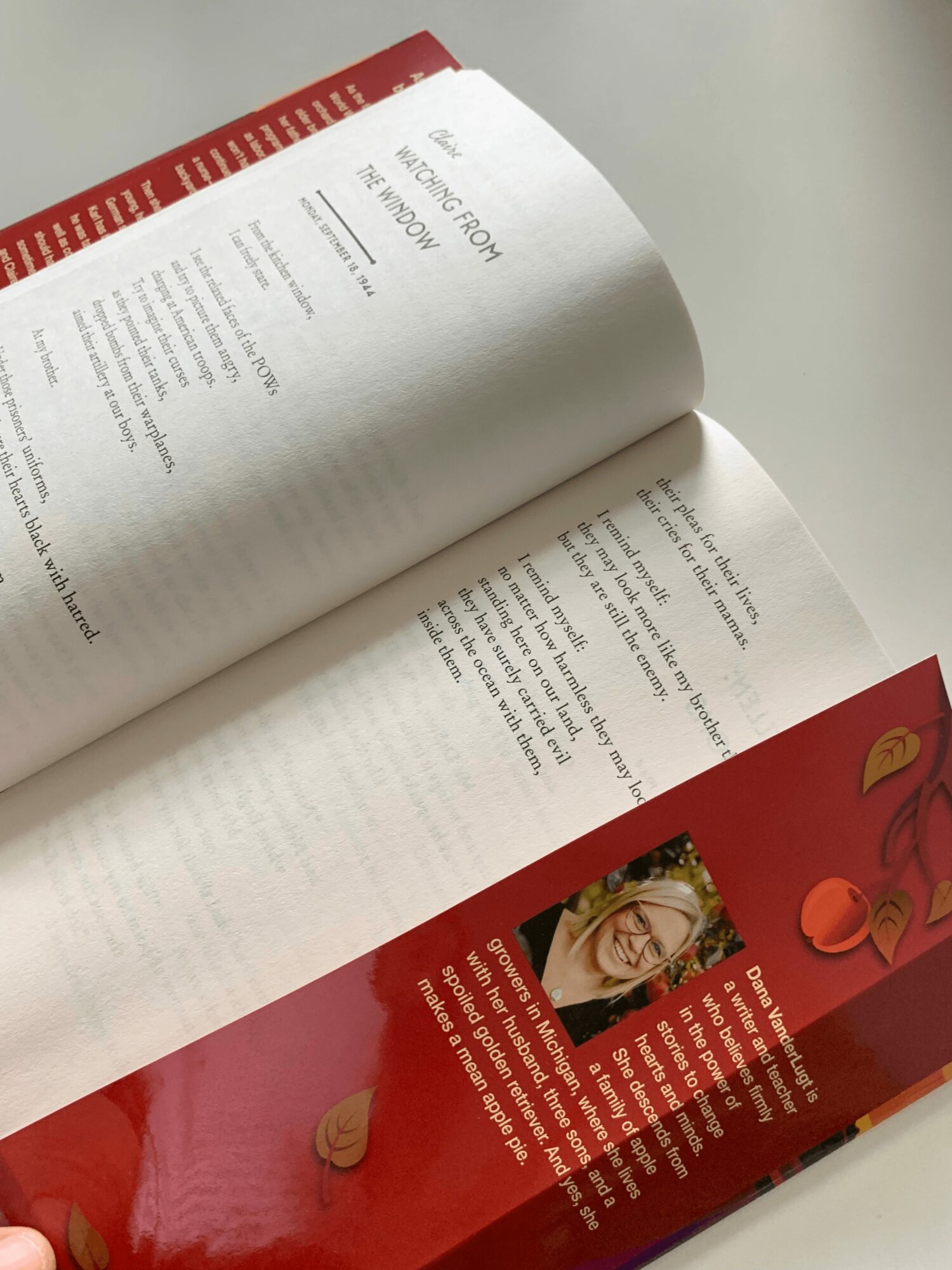

Based on my family history, the book, which is written for readers ages 10 to 110, tells the fictional account of Claire, a 13-year-old girl who longs to enter high school and become a nurse even as she worries for her soldier brother, and Karl, a 17-year-old German POW who’s processing the war as he works on Claire’s family farm.

The roots of the story go back to the apple orchard my grandfather managed for most of his life. I grew up calling the rolling acres “Grandpa’s Orchard,” though technically, the two hundred acres of apples (plus fifty-some acres of peaches, cherries, and plums) never belonged to our family. My dad and his siblings were raised on that farm, and in many ways, I was, too. It’s hard to separate our family history from the acres of rolling land where we picked apples, took tractor rides perched on Grandpa’s lap, built forts, and played with our cousins.

Several years ago, while working on an essay for a college course, my dad mentioned to me a story he had once been told by the owners of the land: that during World War 2, a decade before Grandpa and his young family came to live on the farm, German prisoners had been hired to help pick that fall’s crop of apples. Fascinated by this tidbit of information, I began extensive research on the German POWs who were herded onto once-empty Victory ships returning from delivering supplies to Europe, a solution to the country’s labor shortage.

I learned that from 1943 to 1946, 425,000 POWs—mostly Germans, but some Italians—came to more than five hundred labor camps across the United States. In Michigan, thirty-two base camps housed prisoners plucked out of war and, in many ways, saved by being captured. Most were grateful to give up their guns, relieved to be sent to camps where they were well-fed and outsourced to farms that might give them the task of picking celery, apples, or sugar beets.

Though farmers and their families were warned not to fraternize with the enemies that arrived on their land, those instructions were not heeded carefully. Enemy lines quickly began to blur when people talked and worked side by side. The prison guards who accompanied the POWs to farms—often GIs classified as unfit for combat—were by and large a laid-back crew and quick to turn their heads if the POWs were invited to the farmhouse for dinner, especially if they were invited to partake too.

Though a few ardent Nazis pushed their weight around in the camps, many POWs slowly grew more wary of the German Nationalism diet they had been fed their entire lives, more distrustful of Hitler and the Nazi party after each day spent on American soil.

Like my main character, Karl, near the end of the war, many German soldiers were just teenagers, boys who were mandated to become members of the Hitler Youth and attended schools that included racial science and eugenics as part of their curriculum.

Also, like Karl, the painful and convicting process of disillusionment began for many German POWs the day they sailed into an American harbor and discovered that the country had not, as they were told, been bombed to ruins. Through conversations with Americans, newspapers and magazines made available to them in prison camps, and exposure to films, theater, and books once banned from their viewing, the lies and hatred their lives had been built upon crumbled much like their war-torn hometowns back in Germany.

Details on the POWs who worked inside my grandpa’s orchard are fuzzy and few, but the story, as it was passed on to my dad, goes like this. As the fall sun crept down toward the horizon at the end of their final day during their last shift, the prisoners cried as they were told it was time to leave because they were worried about now being killed by the Americans. However, something never felt right to me about this interpretation of the story, and I found myself doubting its simplicity and assumption.

In many ways, the story of Claire and Karl became my pursuit to add depth, understanding, and complexity to the one piece of a very large puzzle I was given. Claire and Karl’s story is a work of fiction. They aren’t real people, though their lives are based on my family history and stories I’ve read about the soldiers and families whose lives intersected on American soil while the war raged on in Europe. Most historical sources paint a fairly idyllic picture—not perfect, but not adversarial—of this American experiment of bringing the enemy home to do the work left behind while we sent soldiers to Europe.

While I worked hard to maintain historical accuracy, I also hope readers will come to better understand the toll and complexity of war, as well as the dangers of nationalism and blind loyalty. My attempt is not to excuse or justify the horrors of the Holocaust or the evil that soldiers like Karl were wrapped up in but to better understand it and prevent it from happening again. In portraying Karl’s humanity, I hope it can be understood how German youth raised under Hitler’s vile regime were used as his weapons while also becoming his victims.

Claire’s American homefront experience is rooted in my family history as well. Neither my maternal nor paternal grandmother went to school past the eighth grade, as education was often seen as needless for women, who were assumed to have no career expectations beyond that as a mother and homemaker. Both of my grandfathers also dropped out of school after eighth grade, including the grandpa who eventually went on to manage the apple orchard. His father died when he was just a toddler, and his two brothers left to serve in World War 2 when he was about Claire’s age, so he had no choice but to quit school and help his mom run the family farm.

Though a work of fiction, Enemies in the Orchard is as real to me—and I hope for my readers, too—as the apples that grow each fall on the new trees my parents have now planted. Like Claire and Karl, the fall of 1944 planted deep seeds within me: seeds of wonder, sorrow, regret, goodness, pain, and beauty. The roots of those emotions are now wound so tightly together that I couldn’t separate one from another if I tried.

Can you talk to us about the challenges and lessons you’ve learned? Looking back, would you say it’s been easy or smooth in retrospect?

There were several bumps and detours (some more enjoyable than others) along my way to get Enemies in the Orchard published.

First, I wanted very much to get this story right. Though fiction is often easily categorized as “fake,” when writing historical fiction, the writer must be focused on not only getting the historical details correct but also the emotional tenor of the novel. The characters must come to life. This required careful and time-consuming research and reading.

Also challenging was my work as a novelist to be certain I used every word carefully and precisely to create a compelling picture of this complex period of American history. While adults are often surprised — and maybe a bit nervous— to open my book and see it’s written in verse or poetic form, most young readers are not. The verse format has exploded in popularity in recent years in the middle-grade and young-adult markets.

Much fewer novels in verse are written specifically for adults; it’s hard to pinpoint reasons for this. Perhaps older readers are not as tempted by white space, or perhaps they are tainted by negative experiences with poetry when they were younger (which I believe happens when poetry is taught only through the lens of analysis: as if it’s a multiple-choice question to answer correctly rather than a mystery to explore).

But of all the bumps along the way, it was once my manuscript was written that came the most tenuous part of the process — getting the novel published! The writing industry is tough, and I’m grateful for the mentors, coaches, friends, and family who encouraged me when the path was rocky. I am also grateful to have found an agent who treated me and my story with care and walked alongside me during the countless rejections that came my way before I found an editor who took the time to connect with my story.

And finally, I worked on this novel while working full-time in education and raising three young boys during the pandemic. Making time for my writing was a constant battle, but early morning writing sessions when my house was quiet and dark were what kept me going — and gave me the creative space to bring the story to life.

Can you tell our readers more about what you do and what you think sets you apart from others?

Because I worked for more than a decade as a middle school teacher and now work as a literacy consultant at the Ottawa Area Intermediate School District, I care deeply about literacy on several levels.

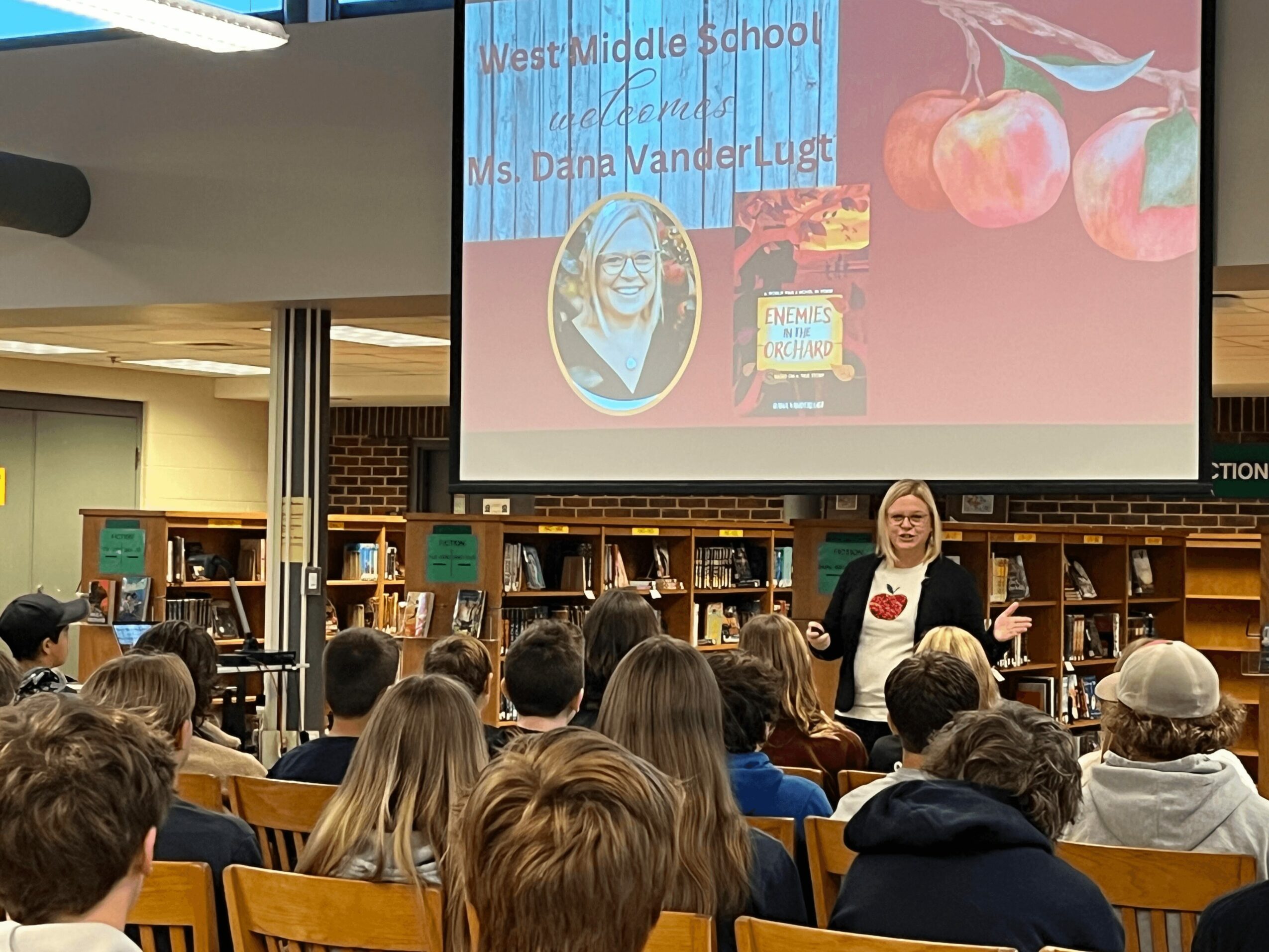

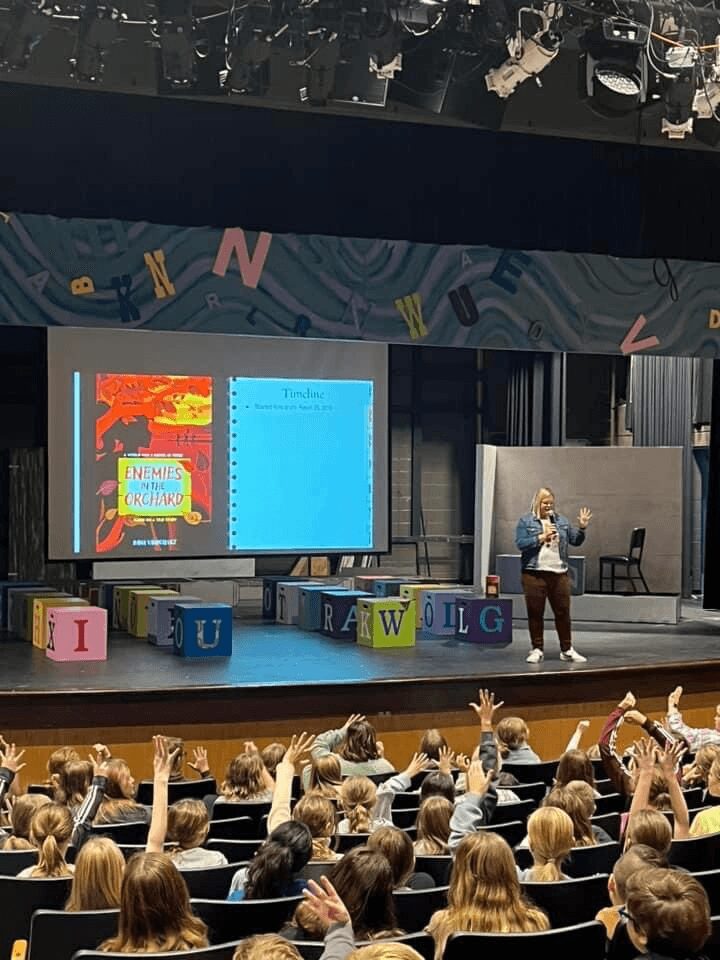

As I wrote this book, I thought of the 8th graders in my classroom and the kind of book I’d want to read and discuss with them. One of my greatest joys has been visiting schools and classrooms and working with teachers as they integrate my book into their curriculum.

I always approach my work through the lens of a teacher and how I might engage students, not only in my book but to be curious, creative, and critical thinkers.

What do you like and dislike about the city?

I love West Michigan for many reasons — the lake, four distinct seasons, beautiful parks, and local businesses (like my parents’ orchard!) that invest in our communities.

And I love discovering and uncovering the stories and histories of the people who live here.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.danavanderlugt.com

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/danavanderlugt

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/danavanderlugtwriter

- Twitter: https://twitter.com/danavanderlugt