Today we’d like to introduce you to Dr. Nicholas F. Russell, Ph.D..

Hi Dr. Nicholas F., we’re thrilled to have a chance to learn your story today. So, before we get into specifics, maybe you can briefly walk us through how you got to where you are today?

My story really begins in the late 1970s when my parents made the decision, before I was born, to move up to the Grand Traverse region from Detroit. My dad was going to the maritime academy there, and besides that, they wanted a better place to raise their kids; Detroit was a crime-ridden city in those days, and Leelanau, where we eventually settled, seemed by comparison a bucolic paradise. Although my dad was Protestant and my mom was Catholic, they wanted to send me to a school where my faith was openly practiced—so Dad compromised, and they sent me to the local Catholic schools. Around the 5th grade, I made an important decision. Academic life really ramped up that year, and I had a challenging homeroom teacher. I wanted to excel at academics, though, so I embraced the new workload and between that and other activities, was kept pretty busy 14 hours per day, 7 days per week. Most of that time was spent on school and homework, because academics always took precedence for me—although I was also a gifted flutist, and my fondest memories of those years are from band class, our annual band trips, and performing at football games.

Despite my emphasis on academics, however, I hated school because it was too easy for me. The assignments kept me busy for long hours, but I wasn’t learning nearly as fast as I was capable of. Although I graduated valedictorian of an 80-something strong class in 2003, I remember only applying to three colleges (and I did even that much only to appease Mom): Michigan Technological University, St. John’s College, and Hillsdale College. Of the three, I eventually decided I wasn’t sure I wanted to be an engineer, which ruled out Tech, and I had to admit I couldn’t afford the tuition at St. John’s. So, my choice pretty much defaulted to Hillsdale.

It was actually a blessing in disguise: Hillsdale turned out to be one of the best things that ever happened to me. Little did I know at the time that Hillsdale was already regarded as one of the top liberal arts schools not only in the country, but also globally. I quickly became enmeshed in the Hono(u)rs Program (the U was much debated) and discovered a wonderful teacher, Dr. Stewart, who in essence, across four years of persistent instruction, forged me into one of the most perspicacious readers there is. He was a historian, and his specialty was showing kids how to read old texts as they would have been understood when they were produced. This involved a great deal of imagination but also tremendous fidelity to facts and details—every insight had to be grounded in the evidence.

As a result of Dr. Stewart’s immersive instruction, by the time I graduated I already had a professional historian’s abilities when it came to the readings. I knew by then that I wanted to be a historian, and I applied to ten graduate schools; I received full-ride offers from three, and of those, I might have chosen Hawai’i but instead picked Tufts University. I didn’t select it because it was a Little Ivy—just as with Hillsdale, I had no idea of the college’s standing before I had gone there—but instead because of the scholar with whom I’d be working: Felipe Fernández-Armesto. I didn’t really know how famous he was at the time, only that I’d read and greatly appreciated a book he’d written about the Canary Islands. I knew I liked his style of scholarship, and it turned out that he also liked mine, because my writing sample, wretched though it was (I still didn’t know how to write very well at that time), I later learned in some way impressed him.

I subsequently spent six years in Boston, where I was a teaching assistant by day and a graduate student by night. I struggled to acclimate to the culture there (most of the people really are quite cold), but nonetheless, I made several life-long friends. I suffered the worst effects of my first health crisis during the second half of my first year there; by spring semester 2008, I was only functional six hours per day because of horrific migraines in my eyes that were caused by light. The rest of the time, I was in a darkened room, in bed. I finally discovered that a prescription drug was causing the problem—a side effect so rare it wasn’t in the drug literature. I stopped cold turkey, and over the course of around eight months, I slowly got better. I thought I was past my most difficult time.

But fate had other plans for me, because in December of that same year I contracted a parasite from bad fish that caused so much bloating it actually herniated my stomach and dislocated a rib. Worse yet, when the rib dislocated, something tore at the junction with the spinal cord, resulting in excruciating vise-like pain wrapping around my left thigh. This was sciatica on steroids, like ten times stronger than what most people experience. I also had a good deal of pain in my lower back and just in general, throughout my left side. The stomach injury, too, was agonizingly painful—despite doctors assuring me I shouldn’t even be able to notice it. After having gone to three different surgeons at three different hospitals, I finally found one who would repair my stomach. Fully a third of my pain had disappeared by the time I woke up in recovery. Meanwhile, the spinal injury caused a diagnostic nightmare: the pain was everywhere—so, where was it coming from? I was going to physical therapy, the gym, the chiropractor, radiology, neurosurgery, the pain management doctor, the acupuncturist, occupational therapy, aqua therapy, and anywhere else I might have had even the remotest possible chance of meeting someone who could help me with what I only belatedly realized was actually a spinal condition. Across the years, I accumulated well over 1,000 medical visits while dealing with these problems.

Despite this massive setback, I continued as a full-time student at Tufts. I kept at the work, making sure to fulfill all my responsibilities. I both researched and wrote the entirety of a surpassingly excellent master’s thesis during spring 2009 and earned my master’s degree by May. I stayed on track to getting my doctorate. In 2013, just after I’d finished my studies at Tufts and arrived at the all-but-dissertation stage, I received news I’d won a matching grant from the Spanish government to study overseas in Spain for a year and conduct research on my dissertation topic. I still had to provide half the money in the form of federal loans, but I went anyway—this was an experience I knew I needed to have in order to be taken seriously as a scholar of Spanish history. I considered it to be a requirement because, as I had discovered at Tufts, I was a gifted instructor; I knew I wanted to teach at university, and to attain one of those jobs, it helps tremendously to have lived overseas.

In Spain, I spent most of my time at the national library and other cultural institutions in Madrid. While there, I met and fell in love with a beautiful Ecuadorian woman, Andreina, whose memory haunts me to this day. She eventually had to go home but, after concluding my research, I visited her and her family in Guayaquil, Ecuador for three weeks in fall 2014. It was extremely romantic, and it quickly became the happiest moment of my life.

My homecoming afterward to the U.S., however, proved to be a dismal, deplorable, and disastrous affair. First of all, my health collapsed because, despite the narcotics I was taking by that time to control the pain in my left side—most of which was still present, six years later—I could no longer “push through” the pain. I found that it must be true of just about everyone that there is a limit to how far you can push. A relatively healthy person will almost certainly never reach his or her limit, but people who are chronically ill often eventually do. Secondly, my kid brother Michael Steven “Demosthenes” Russell, seven years my junior and one of the loves of my life, died by suicide in November 2014 after complications from a head and neck injury. I spent a few long nights playing video games with him in the basement during late October, and those are my last memories of my brother. He had been a tremendously gifted fictional writer—he had won the inaugural National Writers Series prize in recognition of his work—and his loss was significant to the literary world, although few are aware of it.

What followed, in my life, was a season of deep winter. By that time, I was in a huge amount of pain just from being out of bed and upright, so I only got up to go to the pool, since my doctors told me swimming often helps in these cases (it didn’t in mine) and to go to a café to force myself to continue work on the dissertation. I put in 2–4 hours per week, which was the most I could work at the time, for the following two years, eventually compiling a 595-page tome from my research in Spain and Boston and submitting it to my committee. I passed my defense in May 2017 with flying colors, without most of the committee knowing anything at all about the specifics of my circumstances (which means they didn’t pass me out of sympathy). Only Felipe knew the true state of my life. I did so well because, just as Dr. Stewart had taught me how to read, Felipe had taught me how to write in an especially scholarly and efficacious way. My dissertation was truly an admirable piece of work, and I like to believe it might be understood pretty well even by your average American since in my field, we try to write in common language.

When I graduated, there was never any serious question of entering the job market, despite my strong credentials and remarkable finish, because I simply couldn’t handle a 40-hour work week. In fact, I had already by that time entered a long but necessary period of recovery. All other interventions having failed, I was put on heavy medication for several years and was in bed 23/7 because of how sleepy the drugs made me. Something healed in my spine during all that time spent in bed, however, and they were able to take me off the medication without the majority of the pain re-emerging.

I am currently fighting back a resurgence of some of my spinal symptoms, but we caught it early enough that it will not degenerate into the sort of problem it once was in the past. Moreover, novel therapies such as laser treatments, which previously had been unknown and unavailable, have been enormously helpful to me. As a result, my injury no longer defines my life. It imposes certain limitations, but the bottom line is, I’m now able to enjoy things again and have the strength to participate again in normal life activities (which I no longer take for granted!).

During the long period of recovery that has transpired across the past eleven years, I founded Dioskouroi Tutoring as a way of starting to earn an income and to capitalize on my ability to teach. In essence, there are only three things kids need to know how to do by the time they graduate from school: reading, writing, and arithmetic. I can teach any middle schooler, high schooler, or college student how to do the first two of these things to a level of exceptional performance that will earn them accolades all the way through graduate school. And that is where I am today: trying to find my first clients.

Can you talk to us a bit about the challenges and lessons you’ve learned along the way. Looking back would you say it’s been easy or smooth in retrospect?

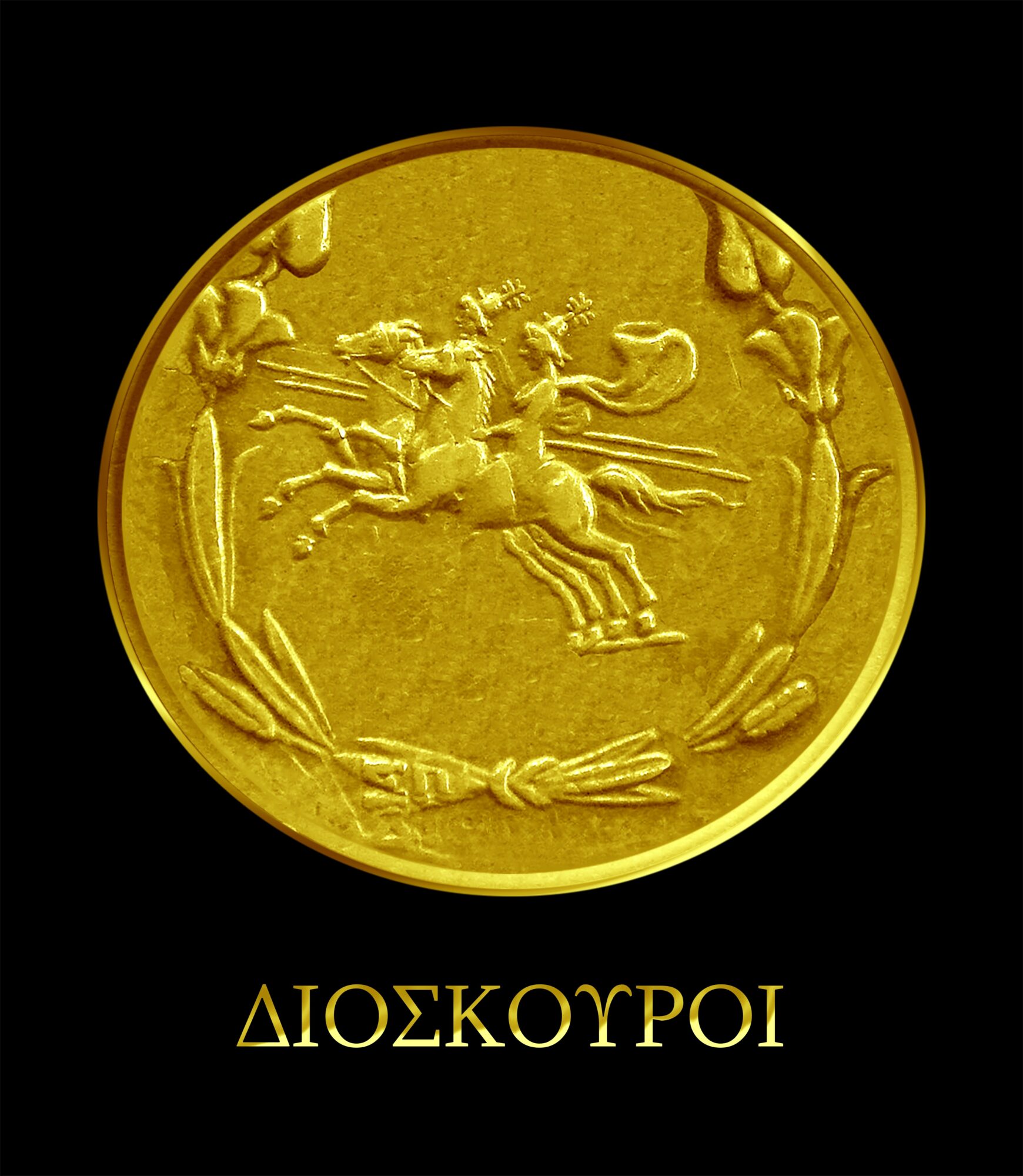

As I mentioned, my struggles with my health have been my most significant challenge. But losing my brother really took the wind out of my sails. Michael was an extraordinary young man, one of the finest men I’ve ever known. I founded my business, Dioskouroi Tutoring, in part to honor his memory. The name draws upon an ancient Greek and Roman story about Castor and Pollux. In the story, although Pollux was divine and Castor was mortal, they were the best of friends. One day, they were rustling cattle when they were caught in the act by the cattle owners, and Castor was killed. Pollux, in anguish, gave up half his divinity in exchange for each of the two of them living every other day, on alternate days, for all eternity.

What’s more, the Romans believed Castor and Pollux were great warriors. They would pray to the two before entering battle because they believed that, at the battle’s pivotal moment, Castor and Pollux would arrive in a spiritual way, mounted on ethereal horses, with lances set, to turn the tide in the Romans’ favor. This is depicted in the logo of my business, which is actually an ancient Near-Eastern coin from the Levant. I’ve modified it to remove the text and colorize it in gold (the original coin is silver), but the imagery is both authentic and ancient. This is truly how the ancients saw the Dioskouroi. The laurel wreaths surrounding the image, meanwhile, connote victory or, more accurately, triumph. I see my brother that way because he’s in Heaven now and has triumphed over his anguishing experience here on Earth.

Alright, so let’s switch gears a bit and talk business. What should we know?

Since 2007, I’ve provided academic mentoring services to young adults, first in Boston and later in Traverse City. I began at my graduate school, Tufts, where I studied history—which is, as I like to say, the “Science of Everything.” History is a special discipline whose practitioners use evidence and logic to make truthful, plainly expressed, written claims about the world we live in. As historians, we teach our students to ground themselves in reality, to think independently, and to form meaningful opinions of their own.

Global historians like me—those among us who examine the history of the world, as a whole—are uniquely positioned to prepare your student for his or her future. This is because of the range and scope of inquiry that is available to us. We can study anything, at any time, in any place, for any reason. No other discipline has this flexibility, and it is because of this specific background that I can offer to your student a kind of general preparation for college—and life—that he or she will not find elsewhere.

Indeed, I provide an educational experience that uniquely honors the core aspects of a liberal arts curriculum. The essence of the liberal arts is to educate someone broadly enough so as to produce a free man or woman, capable of intellectual achievements of his or her own, who is not enslaved to falsehoods and half-truths. Ancient Greek philosophers divided the liberal arts into two sequential stages of learning. In the first and foundational stage, students mastered the Trivium: the arts of grammar, logic, and rhetoric. This is the stage at which reading and writing are learned, and it is also the stage in which I specialize.

The art of grammar, referred to colloquially as “knowledge,” is the underlying background data about a specific subject. Students gain knowledge by means of their five senses and by reading documents and books. The art of logic, or “understanding,” is the science of correct inference. It enables students to gain meaningful insights from the facts they imbibe. The art of rhetoric, or “wisdom,” is the capstone and requires students to combine grammar and logic with techniques of persuasion. Only after students have experimented at length with this volatile and heady admixture will they become effective writers and compelling public speakers.

What makes me unique and special is that I’m the only tutor who knows how to teach advanced reading and writing—and thus, mastery of the Trivium—in an orderly, systematic, holistic, and sequential way. Other teachers merely hope their students will pick up these skills as a natural byproduct of learning course content; in other words, they focus on the content and hope the skills will come on their own. But because I learned from Dr. Stewart, who taught me not only how to read but also how to instruct others how to read, and Felipe, who taught me not only how to write but also how to instruct others how to write, I can teach these skills directly. These two instructors are both incredible gems in their own right, and I combine the best that both men have to offer. Moreover, I dynamically adapt my teaching to the needs of every student. So, there is truly no other teacher like me.

Teaching these skills takes time. The ideal schedule is to meet once per week or every other week for three to five years. By the end, the student will have attained mastery and will no longer need my instruction. They will be able to read and write skillfully and in a spirited and attractive way. That is my purpose: to make myself dispensable, and for the student to become truly independent.

Is there a quality that you most attribute to your success?

Persistence, tenacity, discipline, toughness, resilience, adaptability, and complete devotion to my work are the reasons I was able to come through my health problems with a Ph.D. instead of without it. If I had given up or given in along the way, I would not be where I am today. It’s okay to take a break sometimes. I took lots of breaks because I had to. But the key is to always come back to it and to be singular in your commitment to it—whatever you’re pursuing must be something that’s truly paramount to you. If you cannot make it paramount, you will not be able to complete it. Life will get in the way, and you’ll lose focus and eventually forget about the task that you once thought was so important. You have to put the task before yourself, before your relationships, and before any and all other tasks. You have to sacrifice for it. You have to refuse to take “no” for an answer. It takes stubbornness and tremendous strength of character. So, above all else, during the good times, I’d say one should cultivate virtue and consistency in oneself so as to have the key traits one needs to succeed once hardship arises. You have to prepare in advance to be able to weather evil times. I was fortunate that as a child, I did this intuitively, by instinct, and as a result, had the resolve and the courage as an adult to fight the good fight and achieve success despite adverse conditions.

I would be remiss not also to mention the importance of a support network. When I couldn’t function anymore, my family took me in and cared for me. I also benefited tremendously from the Medicaid program and consistent access to doctors. Without friends, family, and/or institutional support of some kind, people who go through these kinds of experiences will quite simply not be able to make it. So, take care of those around you who are struggling. You might not know it, but you might be all they have!

Finally, I’d like to note that my achievement came at great cost. Putting so much emphasis on one thing can lead to dereliction of duty in other aspects of life. One of the tragedies of my past is that although I successfully earned the Ph.D., some of the sacrifices I made were not only overmuch and not strictly necessary, but also harmful to a person close to me. I missed a big opportunity to help my brother. I was his father-figure and the most important male influence in his life. He would have listened to me. But I did not know the extent and profundity of his suffering because I had been away for so long, and I missed the signs once I got back. By the time I figured it out, it was too late. So, when you see someone close to you suffering, don’t just observe them and think you understand them by watching. Instead, you have to actually ask them detailed questions about what’s going on in their life and what they’re struggling with. Being a little nosy in these instances is wholly appropriate! I wish I had been nosy with my brother, because I firmly and wholeheartedly believe that, if I had, he would still be here today.

Pricing:

- $40/3o minutes

- $50/45 minutes

- $60/60 minutes

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.dioskouroi-tutoring.com

- LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/nicholasfrussell

- Other: https://dl.tufts.edu/concern/pdfs/br86bf768