Today we’d like to introduce you to Jim Burnstein.

Jim, we appreciate you taking the time to share your story with us today. Where does your story begin?

When I was ten, I knew what I wanted to be when I grew up. A lawyer. I graduated from the University of Michigan in 1972, got married a month later at 21, and at the end of that summer my wife Cyndi and I were on our way to Madison where I would attend the University of Wisconsin Law School. It was a long drive, and I began to question my decision as a ten-year-old. What did I really want to be when I grew up? What was I really passionate about? Thanks to my favorite professor, Russell Fraser, the answer was Shakespeare. And it was something he said as an aside my senior year in his complete works of Shakespeare class that I could not get out of my head: “If Shakespeare were alive today, he would be a screenwriter.” I had no idea what that was. I had taken creative writing and play writing at Michigan, and I had never seen a screenplay. But if Shakespeare would have been a screenwriter, shouldn’t I explore this field? But what else could I do? I thought it would be great to teach people who would never learn about Shakespeare except for me… people who didn’t have the privilege of going to the University of Michigan and studying with one of the top Shakespearean scholars on the planet. These were the two goals that were locked in my head as I was walking into law school and walking out after one semester.

Doubt immediately set in, and I decided to go to grad school at the University of Michigan where I could lick my wounds, do some creative writing, and get my Master’s in English in little over a year. It was here after pleading with an assistant at Playboy Productions that I got my hands on the first screenplay I had ever read, Roman Polanski’s Macbeth. It was an absolute revelation, and I studied it like the Rosetta Stone. Now I was ready to go out into the real world and fulfill my two separate goals of becoming a screenwriter and a teacher of Shakespeare to people who would not have it except for me. Cut to:

Six Years Later. I am teaching Shakespeare at night to students from every branch of the Armed Forces at Selfridge Air National Guard Base in Mt. Clemens, Michigan seeking their college degrees and buying my writing time by doing free-lance advertising during the day. My first night at Selfridge I told my military students that they would learn to write essays in freshman composition by reading and discussing Shakespeare’s Macbeth and Othello. They looked at me like I was crazy. I promised them they would love it. It was a war at first, but eventually I won. In time, I would be taking my classes to see their first Shakespeare play at the renowned Stratford Theater, only two hours away in Ontario, Canada. Meanwhile, I had decided that writing TV movies would be my best chance at breaking into Hollywood. The third one I wrote, LEARN TO FALL, a true story about one of my best friends who dropped out of the University of Michigan to become a clown who later volunteered to work with a severely autistic child to escape all the rejection he was receiving as a writer and performer, sails through the system. It lands me offers from three agents, my first option, and a deal at CBS with Columbia Pictures Television producing and Buzz Kulik (Brian’s Song), directing. I think Hollywood is a lot easier than I thought it would be. Then, the star, Timothy Hutton, fresh off Ordinary People, drops out during pre-production, and CBS pulls the plug. I suddenly realized that Hollywood is very difficult. As I crashed and burned, I had no idea that it would be the merging of my two goals, screenwriting and teaching Shakespeare, that would ultimately save my career.

Alright, so let’s dig a little deeper into the story – has it been an easy path overall and if not, what were the challenges you’ve had to overcome?

Overcoming obstacles is the stuff screenplays are made of. Writers must learn to meet challenges the way that their characters do –- with a little help from their friends, mentors, or even adversaries. In my case, an older and wiser friend of mine, Kurt Luedtke, the brilliant executive editor of The Detroit Free Press who decided at age 37 to become a screenwriter and whose first screenplay Absence of Malice earned him an Academy Award nomination, pulled me aside at a party where I am once again licking my wounds and suggests I write a feature on the theory that as long as I’m not getting paid, I may as well not get paid more. Let’s just say that in my inebriated state that made perfect sense. Kurt then asks me if I ever considered writing about my funny experiences teaching Shakespeare to the military. Yes, the thought had crossed my mind. Kurt tells me to come up with a treatment, and if he likes it, he will option it so that I can write the screenplay. I thanked him but told him that we’re friends, and I don’t want his charity. He tells me I’m an idiot. In the morning I wake up and realize I am an idiot. I call Kurt, and here my real education as a screenwriter begins.

After I write the treatment, Kurt teaches me how to write a three-act step-outline. I didn’t know such a thing existed. Then, I write the first draft of Renaissance Man. I think it’s Shakespeare, he thinks it’s crap. He tells me to rewrite it. I am beginning to hate my friend turned mentor. But I rewrite it, and he tells me I clearly don’t know how to rewrite. Then, over a long weekend at his summer place on Lake Michigan, he teaches me how to rewrite. What I really learned was how to think like a screenwriter. It was amazing. When I turned in the third draft, Kurt said, “This isn’t all bad.” And if you knew Kurt, that was high praise indeed. I write one more draft, and Kurt says, “I think we’ve gone as far as your talent will carry us. Let’s get it out there.”

And now after four drafts and three years, luck starts to work in my favor. My young agent decided to go work in development, but on his way out the door he tells his boss, Stu Robinson (who would become one of the founders of Paradigm), he should read Renaissance Man. Stu calls me and says, “I don’t know who you are or where you live (“Is it Chicago?” I say, “That’s close enough”), but from now on I will represent you. There isn’t an ounce of fat on your screenplay. It might take me two years, but I guarantee you I will sell it.” I immediately fly out to meet Stu. He takes me to lunch and asks me the question that will determine my future. “What do you want to do? Move to LA, I’ll set you up with lots of meetings, or go back to Michigan and swing for the fences?” He looks so much like my dad I can’t lie to him. I tell him I can’t afford to move to California. I have a house, two young children, and there’s no way my wife Cyndi would ever give up the teaching job she loves. (And let’s be honest here, she’s a much better Shakespeare teacher than I ever was.) Stu says that’s fine, he reps John Sayles (one of my heroes), and he doesn’t live in LA. All he asks is that when he says I need you to get on a plane for an important meeting, I will do it. I immediately agree.

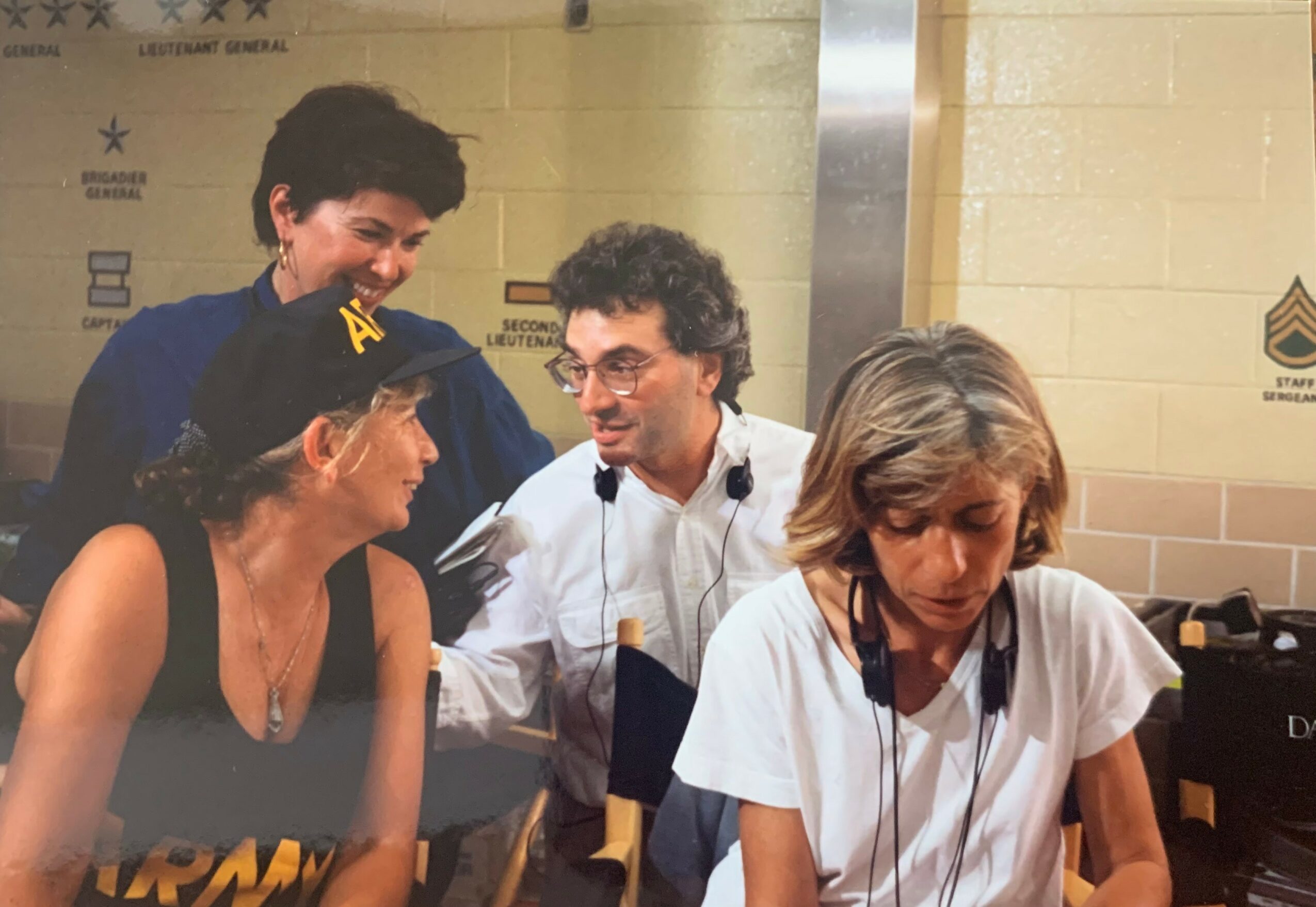

Two years later, I’m meeting with producer Sara Colleton. She asks me if I’m willing to make any changes to Renaissance Man. I’m thinking here it comes. Goodbye Shakespeare. But Sara wants me to focus more on the teaching of Shakespeare, not less. I am thrilled. By the time, I land back in Michigan I have a deal. The next time I meet with Sara, she tells me that I’ve written a wonderful little screenplay, and she’s going to teach me how to write a great big movie. Class was once again in session, and Sara is a terrific teacher. It was her idea, to shift the focus from the Air Force to the Army and set it in basic training. Two drafts later, Fox isn’t interested. I think it’s over, but Sara wasn’t giving up. She optioned the screenplay and drove the turnaround deal that took it to Touchstone at Disney. And two drafts later, one for Touchstone, and one for Penny Marshall, the first director Sara took it to in the wake of A League of Their Own, I had my first film in production in 1993. That’s ten years and eight drafts from when I first started writing Renaissance Man. Everybody tells you that becoming a professional screenwriter isn’t a sprint, it’s a marathon. Nobody wants to believe it, but it’s true.

Can you tell our readers more about what you do and what you think sets you apart from others?

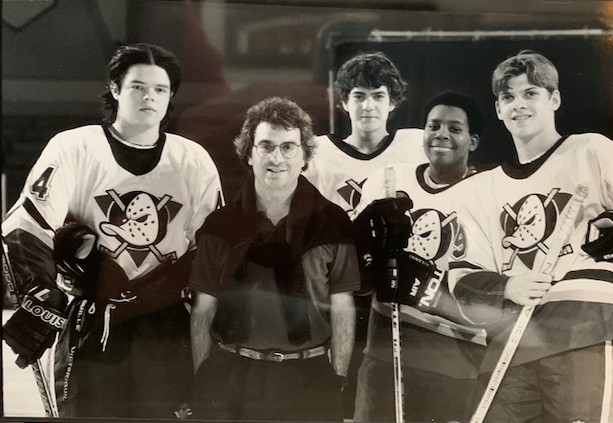

After Renaissance Man came out in 1994 and D3: The Mighty Ducks was in the can in 1995, I thought my teaching days were permanently over. Then the head of the Program in Film & Video Studies at the University of Michigan called and asked if it were true that I lived in Michigan and not LA. When I said yes, he asked me why I wasn’t teaching for them. Honestly, if any other school than my alma had asked, I would have said no. Instead, I said I would teach one screenwriting course, but it had to be three hours on Monday night, so that I could fly to LA for the rest of the week if I needed to. I told my first class of 20 students that they would learn to write a feature screenplay in a single semester. I figured if I could teach Shakespeare to soldiers, I could sure as hell get them to write 100 or more pages. Basically, since I had never taken a screenwriting class myself, I would be teaching them what Kurt and Sara had taught me. I had no idea what to expect, but some of the students were so talented and their first drafts were so good, it blew me away. And I immediately felt guilty. I had not taught them the most important lesson. The rewriting process.

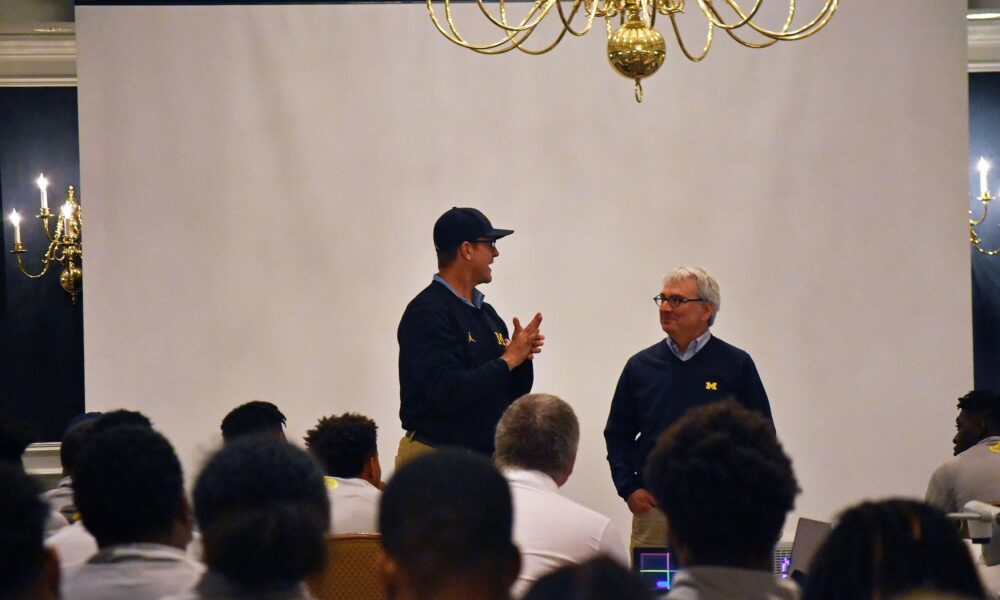

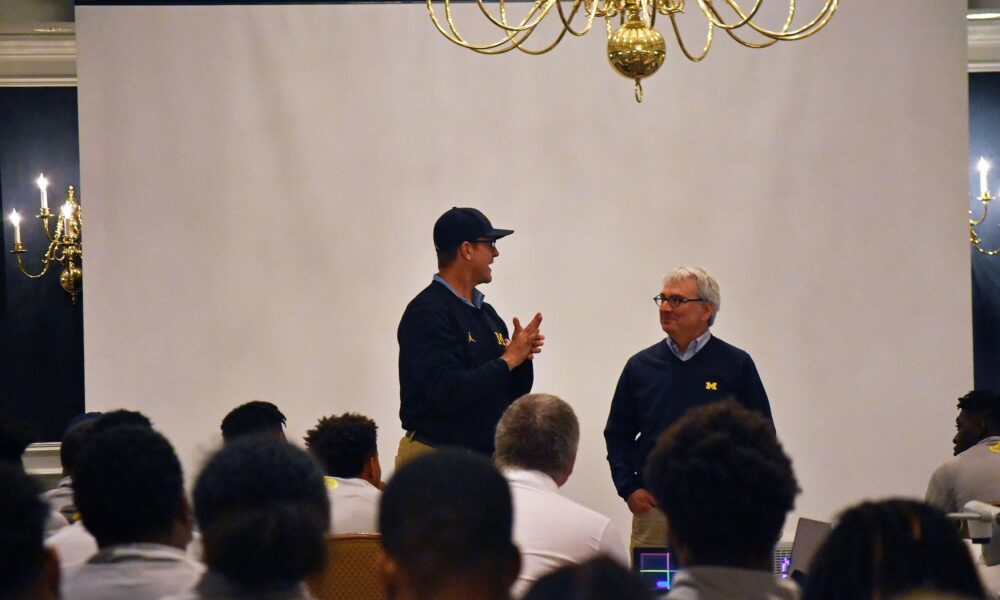

Very shortly thereafter, I was asked by the new head of Film & Video, Professor Gaylyn Studlar, to build a Screenwriting Program that would help us become a department. So, I asked myself what I would have wanted if I were a student at Michigan who wanted to be a screenwriter? First, I needed a rewrite course. Second, I needed a library of screenplays. Third, I needed a visiting artists program that would allow me to bring in the top writers in the industry to talk about their work and careers and conduct master classes. I had seen the effect Kurt Luedtke (who won the Oscar for Out of Africa) had when he came to speak and work with my students. Soon I was flying out to LA to meet with Michigan alums to raise the money for my dream program. And thanks to Robert Shaye, the founder and CEO of New Line Cinema, and Peter Benedek, foundateur of the United Talent Agency, we were able to fulfill every one of my wishes and more with a screenplay library, the Donald Hall Collection, the likes of which I had not seen outside of the Writers Guild in LA, and two visiting artist series that have brought an army of A List screenwriters and television writers, writer-directors, showrunners, and producers to Ann Arbor for almost a quarter of a century. We have expanded from one screenwriting class to now eight courses in screenwriting and television writing, sending our own army of talented young writers to work in Hollywood. Very few have been inspired by my example that you can live in Michigan and work in Hollywood.

The truth is, I would not have been able to keep teaching and have the great pleasure of watching all three of my kids, Gabe, Devin, and Jake go through the University of Michigan if I had not found a collaborator who would allow me to maintain my screenwriting career. I found the perfect partner in Garrett K. Schiff who was born and bred in LA and happens to me my younger cousin. I didn’t believe at first that I was capable of collaborating, but Garrett taught me otherwise. Together we have sold screenplays to every major studio in Hollywood and had three movies made, Love and Honor starring Liam Hemsworth and Teresa Palmer, Ruffian (ESPN/ABC) starring Sam Shepard, and Naughty or Nice starring George Lopez (ABC). This year Dark Horse published our first graphic novel for children, Ham-let, a pig prince who has to save his animal kingdom from his evil stepfather. Thank you again, Professor Fraser.

Is there a quality that you most attribute to your success?

If you had asked me this question when I was young, I would have said the most essential quality to my success was my competitive nature. And I would have been wrong. All my competitiveness did was keep me in the game. I grew up loving to play all sports, and I didn’t like to lose. So, when people told me I had to move to LA to become a screenwriter – and even then, the odds of making it were very low – I would say to myself, “Thanks, you just make the game a whole lot more fun.” What I didn’t understand was that learning how to accept rejection was the key to playing in the big leagues of Hollywood. I took it personally at first, and that was just plain dumb.

I had to learn that the most important quality to succeed in any field was perseverance. How much rejection can you take and keep moving forward? You have to be a little like Rocky Balboa in the original Rocky. Sylvester Stallone is really telling his own story about all the rejection he took as a “bum” of an actor and yet kept moving forward. We cheered for Rocky because we understood he was fighting for his own self-esteem, just like the rest of us. There’s a reason we always cheer for the underdog, whether it’s Rocky or Erin Brockovich. They refuse to quit. They embody the essential quality of perseverance.

But I also learned that perseverance is all about the willingness to improve. In short, I had to “up” my game if I wanted to fulfill my potential. Oddly enough, it was the great Gordie Howe, the Babe Ruth of hockey, who gave me the key to becoming a professional. In my earlier days as a freelance advertising writer, I had the chance to work with my idols growing up, Howe, Ted Lindsay, Alex Delvecchio, and all these legendary Detroit Red Wings at a fantasy hockey camp that I helped create in Port Huron. Gordie knew I wanted to be a professional screenwriter, and he told me, “You must never stop being a fan of the game you’re in.” In other words, don’t look at your competitors as lucky or undeserving of their success. Envy will only eat away at your soul. Admire and learn from what your “rivals” are doing.

This really hit home after I already had two movies made and I read Cameron Crowe’s screenplay for Jerry Maguire. I realized right away that Crowe was playing at a level that I had not yet reached. He was simply better in every aspect of screenwriting and storytelling. I read the screenplay and watched the movie over and over, studied Crowe’s moves, and improved. It is no surprise that I have used the screenplays for Rocky, Jerry Maguire, and Susannah Grant’s Erin Brockovich many times in my screenwriting courses. You want to be a screenwriter, read the people whose work you admire. And never stop being a fan. When you see Greta Gerwig’s Ladybird or Jordan Peele’s Get Out, get your hands on their screenplays and study them like the Rosetta Stone. The fact is, becoming a screenwriting professor taught me how to be a better screenwriter. Perseverance ultimately is not about merely taking a punch. It’s learning how to deliver a better punch of your own. If you are lucky enough to have the chance to help others fulfill their dreams, you will enjoy the fruits of your perseverance even more. After all, if people like Sara Colleton and the late Kurt Luedtke and Stu Robinson hadn’t stuck with me, we wouldn’t be having this conversation.

Contact Info:

- Instagram: Jim Burnstein

- Linkedin: Jim Burnstein

Image Credits

Mary Lou Chlipala